The Syrian War Is Actually Many Wars

President Donald Trump is ordering U.S. strikes against government targets in Syria after a suspected chemical attack.

The Middle East is a “troubled place,” President Donald Trump said Friday night as he described his decision to use America’s “righteous power” in a retaliatory attack against government targets in Syria following a suspected chemical attack there.

Syrian President Bashar al-Assad seems to have won the civil war in his country—but that doesn’t mean peace is coming. In fact, the conflict seems to be escalating—fueled by the many outside powers who have joined the Syrian battlefield with interests of their own.

“If you look at the literature on civil wars, it tends to suggest that the more foreign powers involved, the more difficult it is for a civil war to end—because most of those powers aren’t willing to quit until either they are exhausted or their claims and desires have been met,” said Christopher Phillips, author of the book The Battle for Syria: International Rivalry in the New Middle East. “And because a lot of them are backing proxies, the cost isn't necessarily that high.”

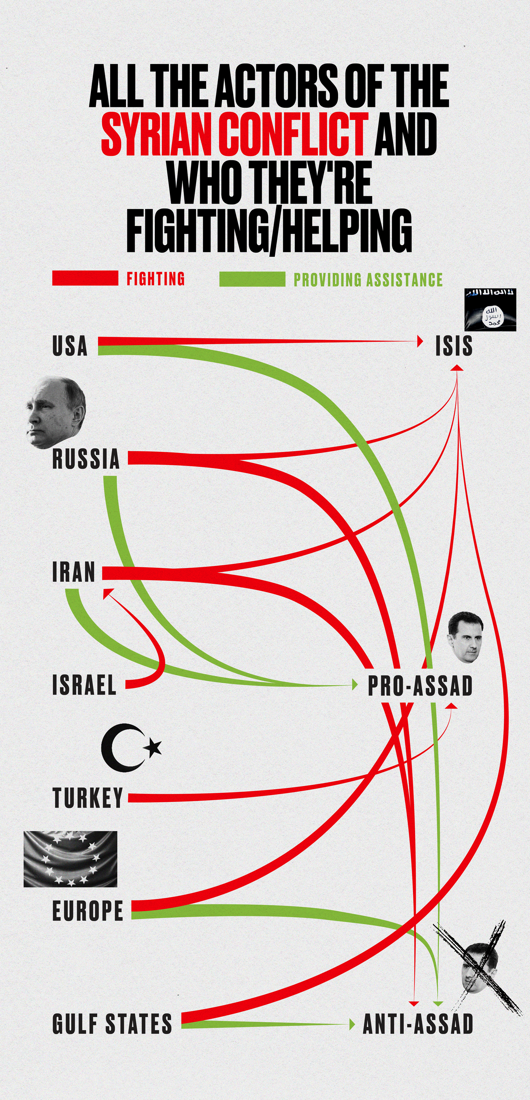

Over the seven years of Syria’s war, it has sucked in numerous other countries, who have attempted to shape the conflict with every tool from bombing to mercenaries to special operators to weapons shipments to money. The war has grown ever more complicated and more deadly over time, and Syria’s future is now largely being determined outside of its borders. Who is fighting in Syria now, and why?

The United States of America

The United States is in Syria mainly because of isis. At a recent event in Washington, the U.S. envoy to the anti-isis coalition Brett McGurk spelled this out: “We are in Syria to fight isis. That is our mission and our mission isn’t over, and we’re going to complete that mission.” More recently, Secretary of Defense James Mattis told Congress that the United States was not there to take sides in the broader civil war.

But it is also pursuing other interests there—including containing Iran’s influence, and also punishing the use of chemical weapons. “The United States has ... pursued [its interests] with different importance in different emphasis at different times,” Phillips said. “And that’s one of the reasons why U.S. policy has been largely unsuccessful.”

Prior to the rise of isis in 2014, the United States generally sought to contain the conflict, as efforts at international diplomacy failed to resolve it. The Obama administration advocated for Assad to step aside, but was reluctant to send weapons or funds to the rebels opposing him, out of fear that they would fall into the hands of Islamists and radical jihadists among them. In 2012, Obama also famously set a “red line” regarding chemical weapons, saying that their use would change his calculus on U.S. strategy there. But when Assad used sarin gas on civilians in 2013, Obama opted, instead of using force, for an agreement with Russia to destroy Assad’s stockpiles of chemical weapons. The U.S. started bombing Syria for the first time a year later, hitting not regime targets but targets associated with isis. It has continued bombing ever since.

Then came the suspected chemical attack of last weekend, to which Trump retaliated with strikes against the regime, as he did to a similar attack last year. This means the United States has once again expanded its mission beyond counterterrorism.

Europe

European countries like France and Britain are also in Syria because of isis. These countries’ policies have hewed largely to those of the United States—including, for the first time on Friday, participating in retaliatory attacks against Assad’s alleged use of chemical weapons—though the difference is that Europe is also grappling with the refugee crisis Syria has produced. The crisis has altered political dynamics on the continent, helping fuel electoral successes for far-right parties that oppose immigration.

“To face these threats, what we need is to stabilize Syria, and to stabilize we need a credible political transition,” Gérard Araud, the French ambassador to Washington, said this week. “The goal of the West should be political engagement with Russia, Turkey, [and] Iran with a view of political transition.” Both France and the U.K. joined the U.S. military action against Assad’s latest alleged use of chemical weapons.

Russia

Russia is in Syria to protect the Assad regime from rebels it sees as terrorists, and project influence in the Middle East. Its military intervention in September 2015 ensured Assad would not only reverse his losses, but regain much of Syria. America’s scattershot approach to Syrian policy helped, as did the metastatic spread of isis that created a common enemy for both the pro- and anti-Assad camps.

Russia’s relations with the Syrian regime date back to the Cold War. Syria is home to the only Russian naval base on the Mediterranean (in Tartous). But those considerations aside, Russia is also genuinely concerned about the growth of Islamist groups that have emerged in other Arab countries where a strongman has been replaced by chaos. Perhaps most important from its point of view, though, is that the Syrian conflict shows the world that Russia is back.

“It’s very important for [Russian President Vladimir Putin] to use Syria as a platform to project Russian power—and give the impression that just as the Soviet Union was a major player in the Middle East, so is post-Soviet Russia,” Phillips said.Indeed, if there is an indispensable power in Syria it is Russia. Moscow has close relations with virtually all of the major actors in the conflict except the United States: Iran, Syria, Turkey, and Israel. It is playing an increasing role in brokering some kind of an understanding between Israel and Iran on what type of Iranian presence in Syria Israel will tolerate, Ofer Zalzberg, a senior analyst for Israel/Palestine at the International Crisis Group, told me. “My analysis is that the more these incidents [in which Israel responds inside Syria with its military to Iranian actions] will become frequent ... Russia [will move] into an increasingly active position,” he said. It is not clear, though, that Russia has the influence to persuade Assad to stop using chemical weapons on his own people.

Iran

Iran is in Syria to protect the Assad regime, and also to use its proxies to menace its archenemy Israel from a neighboring country. Syria has been an Iranian ally since Iran’s 1979 Islamic revolution, and was the only Arab state to support Iran during its brutal war with Saddam Hussein’s Iraq in the 1980s. But loyalty aside, Syria also is of strategic value to Iran, because it acts as a buffer against any military action by Israel or others from its west, as well as an outpost through which it can arm and supply Hezbollah to put pressure on Israel and contain its military actions in the region.Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia is in Syria—primarily by financing the rebellion—to oppose Iran. It funded the Syrian opposition precisely because Iran, its main regional rival, had dug in. In the rebellion against Assad’s minority sect by Saudi Arabia’s Sunni coreligionists, Saudi Arabia saw an opportunity to turn Syria from a pro-Iranian state into a not-pro-Iranian state. Turkey and Qatar, too, saw in the uprising an opportunity to transform Syria into a friendlier state, and funded groups with links to the Muslim Brotherhood. Mohammed bin Abdulrahman al-Thani, Qatar’s foreign minister, told reporters in Washington Thursday that Assad was a “war criminal” who “deserves to be prosecuted.” He called for a diplomatic process that would lead to a power transition—an idea that has repeatedly been floated, but which Assad, who has won back much of the country, doesn’t have much incentive to pursue.Israel

Israel is in Syria to oppose Iran. For years, its border with Syria was its quietest frontier—despite its poor relationship with Assad and his father, Hafez al-Assad. But Israel has watched Iran’s growing influence there with alarm. It fears Tehran will establish permanent military bases inside Syria, and that Iran, along with its militia Hezbollah, will remain near the border with Israel and construct offensive capabilities such as bunkers that can be used in a future conflict with the Jewish state. Israel has struck inside Syria dozens of times during the conflict, most recently on Monday when it attacked a military base where Iran and its proxies are active.Turkey

Turkey is in Syria because of the Kurds. At the start of the conflict, Ankara strongly opposed Assad, who was previously a close Turkish ally. Turkey supported groups opposed to Assad, including Islamists. But one unintended consequence of the Syrian conflict—and as well as the war in Iraq—was the rise of the Kurds. They quickly became one of the most effective fighting forces in Syria, helping the U.S. in the successful fight against isis. Some of the Syrian Kurds are allied with the Kurdistan Workers Party, a group that operates inside Turkey and which Ankara regards as a terrorist organization. When the Kurds established a successful enclave in Syria, Turkey quickly sent its troops across the border and seized the town of Afrin, which is west of the Euphrates River where Russia has control. It has also threatened the town of Manbij, where U.S. troops are present along with Kurdish fighters. For now, Turkey seems to have traded its opposition to Assad with its antipathy toward the Kurds.These are only the international powers in Syria; this analysis doesn’t even account for the various factions among the opposition and within the regime. But it’s the outside powers who will determine the next phase. And regardless, the Syrian people will pay most of the cost.

“Even if the war ends,” Phillips said. “Syria will be unstable for quite some time.”

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario